Perimenopause, What’s Really Going On-Part I

In my practice about 40% of my patients are women in the 35-50 age range. This means that in addition to treating orthopedic complaints, I am helping many women address the symptoms associated with perimenopause.

I’m using part one of this series to look at this process from a Western medical perspective. I will reprise an earlier-written article on menopause from a TCM perspective in Part II.

What is Perimenopause?

Perimenopause is a natural process that marks the gradual end of the reproductive phase of a woman’s life. It eventually leads to menopause.

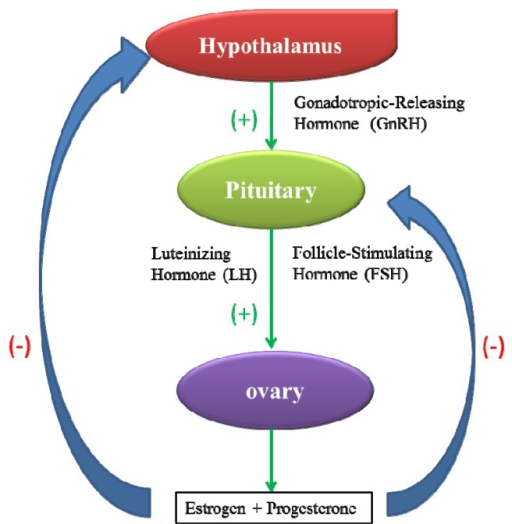

Symptoms of perimenopause appear when hormone levels rise and fall unevenly throughout the course of the menstrual cycle. Estrogen, progesterone, and pituitary hormones—luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)—can rise and fall outside the normal range, producing symptoms including mood changes, headaches, fatigue, and irregular menstrual cycles.

Perimenopause is directly correlated with reduced ovarian function and a loss of female gametes (eggs).

Hormones can fluctuate substantially during this time. Estrogen and progesterone—the primary regulators of the menstrual cycle—can fall too low or become too high depending on what stage of the cycle a woman is in and which ovarian functions are compromised.

The menstrual cycle is regulated by the HPTGA axis—a collection of organs/glands working together to regulate the fluctuations of female hormones throughout the cycle as well as stress hormones.

As women age and the number of eggs in the ovum decrease each month, it results in major shifts in the hormone balance—stemming from a reduced ability for the ovaries to produce both estrogen and progesterone.

The hypothalamus—the controller of the HPTA axis and therefore the menstrual cycle—loses control over the hormone cycle, leading to extreme hormonal fluctuations. These fluctuations are what cause most of the problems during perimenopause.

The HPTA eventually adapts to the change in ovarian function, which is why most symptoms experienced during perimenopause will eventually go away after reaching menopause.

The symptoms associated with these changes in hormone balance can vary significantly from one woman to the next.

The HPTGA Axis is a Hormonal Feedback Loop

The female hormone cycles are carefully orchestrated by the brain and endocrine organs in the body (the ovaries, thyroid, and adrenal glands).

It works like a climate control system—when the temperature drops below a certain level, the thermostat kicks in and sends a message to the heater to increase the temperature. Once the heat reaches the desired level, the thermostat stops sending messages to the heater—so it shuts itself off.

The body works the same way with hormones.

When estrogen levels drop too low, the hypothalamus (the thermostat) kicks on and tells the ovaries (the heater) to turn on and release more estrogen into the system.

Once estrogen reaches the desired amount, the hypothalamus stops sending this message and the ovaries stop releasing estrogen. The same thing happens with progesterone as well.

Using feedback loops like this allows the brain to keep tight control of our hormones.

This axis relies on this feedback cycle to keep all hormones in balance.

The HPTA Organs & Its Individual Roles:

- The hypothalamus (responsible for controlling hormone cycles)

- The pituitary gland (responsible for communicating with glands listed below)

- The thyroid gland (responsible for controlling metabolism and weight changes)

- The ovaries (G=gonad) (responsible for manufacturing female hormones)

- The adrenal glands (controls stress hormones)

The HPTGA Axis and Perimenopause

Now imagine your thermostat sends a message to turn the heat up, but the heater doesn’t respond, or is slow to respond.

This is what is happening during perimenopause. The hypothalamus sends messages to the ovaries to produce either estrogen or progesterone (depending on what part of the cycle the woman is in). If the ovaries don’t respond, the hypothalamus must send a louder signal to the organ to kickstart the process.

The delayed response, and often complete lack of response is what leads to the severe fluctuations in hormones. The hypothalamus is losing its ability to regulate these hormones effectively — allowing them to rise and fall out of control.

The Female Hormone Cycle

If the balance of women’s hormones stayed exactly the same all the time, this system would be much easier to regulate. However, this isn’t the case.

The female hormone balance constantly changes over the course of the menstrual cycle. Estrogen, progesterone, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and prolactin fluctuate dramatically over the course of the month.

It’s these fluctuations in hormones that control the fertility cycle of a woman.

Stage 1: Follicular Phase

→ The first two weeks of the menstrual cycle.

→ Purpose: To regulate

The follicular phase begins with a drop in progesterone and estrogen — causing the uterine lining to shed and prepare a clean slate for a fresh egg in the next cycle.

Over the first 3 or 4 days of the cycle, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland release a hormone called FSH (follicle stimulating hormone), that tells the ovaries to form a follicle — a specialized structure made up of 15-20 eggs that merge together. This follicle is responsible for manufacturing most of the estrogen in the body.

During this stage, a new egg is released into the reproductive tract to prepare the body for fertilization. The newly formed follicle then starts releasing estrogen, causing estrogen levels to gradually increase over the next couple of days.

Stage 2: Luteal Phase

→ The last 2 weeks of the menstrual cycle.

→ Purpose: To create an environment in the uterus ideal for fertilization.

During the luteal phase, the hypothalamus sends another surge of hormones (LH and FSH) to the ovaries. These hormones cause the follicles to change form and begin releasing progesterone. Progesterone causes the uterine lining to thicken and prepare for implantation of a fertilized egg.

Once the surge of LH and FSH is finished, the corpus luteum begins to disappear, bringing both progesterone and estrogen levels down with it.

As these hormones begin to decline, the uterine lining starts to shed and the process begins all over again.

Perimenopause & the Hormone Cycle

Perimenopause begins when the ovaries start to run out of eggs.

Without the release of an egg, the next stage of the hormone cycle can’t begin.

The brain releases FSH to stimulate the release of an egg. If the ovaries can’t respond, the hypothalamus sends another rush of FSH to try and kickstart the ovaries. Sometimes it’s successful, other times it’s not.

As time goes on, unsuccessful attempts become more common — eventually leading to complete halt of the cycle (menopause).

Perimenopause begins as the ovaries lose their responsiveness to the hypothalamus. The lack of control can result in low hormone levels (when the ovaries don’t respond), and excessive hormones (when they keep producing hormones even after the hypothalamus tells them to stop).

This leads to delays in the menstrual cycle and major shifts in the balance of female hormones. The primary cause the loss of ovary function is age — usually beginning around the fourth or fifth decade of life. Women have a set number of eggs, predetermined from birth. Eventually, all women will run out of eggs completely — resulting in a total loss of ovarian function (menopause).

What Happens During Perimenopause?

The first signs of perimenopause is lengthened or skipped menstrual cycles.

As ovarian function declines, it becomes harder for the hypothalamus to control the follicular and luteal phases. This can cause either stage to persist longer than normal — resulting in longer cycles.

Many women report their regular 28-day cycle gradually turns in to 30, 32, or even 34-day cycles over time.

As the supply of eggs in the ovaries declines further over time, the shift of hormones during each phase becomes even slower. The hypothalamus is forced to surge FSH and LH in an attempt to kickstart the process again — often unsuccessfully [5].

Surges of LH in the luteal phase is the main causes of hot flashes [1].

Other symptoms also become more common as the shift in hormone balance becomes even more severe. These symptoms can vary depending on which hormones are most affected.

Estrogen Excess Symptoms:

- Fluid retention

- Excessive menstrual bleeding

- Premenstrual syndrome

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Formation of fibroids

- Irregular menstrual cycless

Progesterone Excess Symptoms:

- Headaches

- Mood changes

- Low libido

- Hot flashes

- Irregular menstrual cycles

- Weight gain

- Fibroids

- Thyroid dysfunction

Causes of Common Perimenopause Symptoms

1. Weight Gain

The main cause of increased weight gain during perimenopause is low estrogen levels.

This is because estrogen has a protective effect on the metabolic system of the body — helping to regulate blood sugar levels and thyroid function. As estrogen levels decrease, complications like metabolic syndrome become more common [2].

Metabolic syndrome involves an inability for the body to control blood sugar levels effectively. As blood sugar levels rise, the liver needs to step in and convert the excess into fat to protect the body from high sugar levels — which can be damaging to the heart, kidneys, and brain.

As this sugar is converted to fat, it’s stored around the internal organs of the body—leading to increased weight gain, especially around the middle.

Studies confirmed this in both animal and human studies by giving estrogen to menopausal females—leading to a lower incidence of type II diabetes, and less weight gain [3].

2. Mood Changes

One of the most common symptoms of perimenopause is changes in mood. This often includes periods of depression, anxiety, and irritability.

Extreme fluctuations in estrogen levels are the primary cause of this symptom.

Research has confirmed that estrogen receptors can be found throughout the brain. This hormone is involved with the regulation of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, GABA, and acetylcholine [4]—all of which are intimately connected to the regulation of our mood.

As estrogen levels decline during perimenopause, the brain enters a period of “estrogen withdrawal”. This can have many effects on the brain, but the main result is a loss of serotonin function—which is a critical component in the regulation of our mood.

It can take a long time for the body to adapt to the loss of estrogen levels and restore normal regulation of mood and cognitive function.

3. Irregular Cycles

Irregular cycles are usually the first sign of perimenopause.

A normal cycle is about 28 days—however, this can vary from one woman to the next. An irregular cycle is defined as a change from the norm for the individual woman.

This can involve longer, or shorter cycle lengths or even a complete absence of menstruation for one or more cycles. Other changes can include excessive or abnormally low blood flow during menstruation.

A. Cycle Length Changes

Skipping periods during perimenopause is very common. This symptom is sporadic at first, but increases as time goes on—eventually leading to a complete loss of a menstrual cycle.

Menopause is diagnosed once there has been a complete lack of a menstrual cycle for 12 months or longer [10].

The cause of irregular cycles is a direct result of the loss of ovarian function. If the ovaries can’t form a follicle — it can’t produce estrogen. In many cases, the ovaries will still be able to form a follicle and keep the cycle going, but it takes more stimulation from pituitary/hypothalamus hormones (LH and FSH) to get it done.

This sluggishness by the ovaries to produce a follicle can lead to longer menstrual cycles.

Other times, the corpus luteum will degrade faster, resulting in a loss of progesterone and estrogen sooner in the cycle — leading to shorter overall cycle lengths.

B. Changes in Blood Flow During Menstruation

Another common change in menstrual cycles during perimenopause is only noticed during the menstruation stage.

Changes in estrogen and progesterone ratios can cause both excessive blood flow or abnormally low blood flow during menstruation.

Progesterone builds the uterine lining up, and estrogen tells it to shed (among other things). Generally speaking, if estrogen is much higher than normal compared to progesterone, it will lead to excessive bleeding as the uterine lining is shed.

Conversely, if progesterone levels are too low, the uterine lining won’t build up as thick as normal—leading to less material to shed during menstruation and thus less blood flow. This often brings other qualities like the formation of dark clumps during menstruation as well.

Migraine Headaches

A common and often debilitating side-effect of perimenopause is headaches —often severe migraine headaches.

A study involving 1436 women in various stages of perimenopause and menopause found that nearly 17% of women in perimenopause experienced migraine headaches. 67% of these women reported improvement or complete remission of these symptoms following menopause [6].

There are two causes for this: estrogen withdrawal as estrogen levels drop, and major fluctuations of the ratio between estrogen and progesterone.

Estrogen is closely associated with the balance of various neurotransmitters in the brain, especially serotonin [7]. Specifically, estrogen increases serotonin production and reduces its breakdown in the brain. The body accounts for this effect when regulating serotonin levels.

As soon as estrogen levels decline, the brain needs to adapt to keep serotonin in balance—which can take several months or years.

This is why so many women experience migraine headaches that align with menstruation—the part of the reproductive cycle where estrogen levels are at their lowest.

Until the body adapts to the change in estrogen, serotonin levels may decline within the brain. Low serotonin levels are closely linked with the formation of migraine headaches. This has been proven in animal studies using compounds that block serotonin [8], as well as human trials using serotonin-enhancing drugs to treat migraine headaches [9].

5. Other Side-Effects

There are a host of other side-effects of perimenopause. These symptoms can vary from one person to the next depending on factors including diet, level of exercise, and how the balance of hormones has shifted.

Low estrogen remains one of the main causes of perimenopausal symptoms — however, other hormones can trigger symptoms as well. Progesterone, prolactin, and even testosterone are all affected during perimenopause. Changes in all of these hormones can result in side-effects.

Other side-effects of perimenopause include:

- Heart palpitations

- Insomnia

- Bloating/swelling

- Nausea

- Night sweats

- Breast tenderness

- Decreased fertility

- Loss of bone density

- Mood changes

References

- Tataryn, I. V., Meldrum, D. R., Lu, K. H., Fruraar, A. M., & Judd, H. L. (1979). LH, FSH and skin temperature during the menopausal hot flas. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 49(1), 152-154.

- Greendale, G. A., Lee, N. P., & Arriola, E. R. (1999). The menopause. The Lancet, 353(9152), 571-80.

- Davis, S. R., Castelo-Branco, C., Chedraui, P., Lumsden, M. A., Nappi, R. E., Shah, D., … & Writing Group of the International Menopause Society for World Menopause Day 2012. (2012). Understanding weight gain at menopause. Climacteric, 15(5), 419-429.

- Sherwin, B. B. (2003). Estrogen and cognitive functioning in women. Endocrine reviews, 24(2), 133-151.

- Santoro, N., Brown, R., Adel. T., & Skurnick, H. (1996). Characterization of reproductive hormonal dynamics in the perimenopause. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 81(4), 1495-1501.

- MacGregor, E. A. (2009). Migraine headache in perimenopausal and menopausal women. Current pain and headache reports, 13(5), 399-403.

- Martin, V. T., & Behbehani, M. (2006). Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis—part I. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 46(1), 3-23.

- Brewerton, T. D., Murphy, D. L., Mueller, E. A., & Jimerson, D. C. (1988). Induction of migrainelike headaches by the serotonin agonist m‐chlorophenylpiperazine. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 43(6), 605-609.

- Moja, L., Cusi, C., Sterzi, R., & Canepari, C. (2005). Selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for preventing migraine and tension‐type headaches. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3).

- McKinlay, S. M., & Jefferys, M. (1974). The menopausal syndrome. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 28(2), 108-115.